Southern Railway’s ability to engage directly at a human level with Eddie is not new – in fact it employed the UK’s first ever PR officer in 1925, John Elliot.

This week saw the making of a new hero and internet sensation Eddie. The 15 year-old was on work experience and was given the reins of Southern Railway’s Twitter account, and in return gave the train operating company a much-needed PR boost.

He instantly became a hit, answering all manner of questions, ranging from what to have for dinner, who was going to win Love Island, and of course the air speed velocity of an unladen swallow. Eddie received supportive words and GIFs, and his original thread was retweeted over 1,700 times.

It showed a very positive side to the unsung heroes of the railway, the social media teams. Often embedded with control teams, they have access to authoritative information about how trains are running and where problems lie. As a result they can get answers to customers’ questions sooner, but also provide feedback directly to the control team and the crews out in the field, running the actual railway.

Twitter is a particularly powerful tool here for its simplicity; I have a list dedicated to the rail companies I use. Consulting it in the morning before I leave for the station is much quicker than checking each individual website.

However, it’s not all plain sailing for these social media teams. When problems do occur, the sheer volume of incoming tweets will surge. Thick skins are needed to handle both trolls and those who are abusive. Passengers are naturally frustrated when there are delays and cancellations, ultimately a train ticket is still a promise to get you there and it costs money. However, there’s not really any excuse for the personal abuse that some experience – even on Southern where the service has been wrecked as a result of a long-running industrial relations issue.

The screens and d evices shield us from the faces and feelings of the real human beings doing the typing at the other end. And up to now nobody has really had sight of these teams.

evices shield us from the faces and feelings of the real human beings doing the typing at the other end. And up to now nobody has really had sight of these teams.

But along comes Eddie and suddenly it shines a light on it and there’s maybe, just maybe, a little bit more understanding of them simply by seeing their faces and inside their office space. #AskEddie was a risk, and it didn’t come without some unwanted questions and attention, but basically, it was a hit and if it’s a hit on social media, conventional media often follow. Eddie was on Radio 1, and covered by traditional news including BBC and Sky. The role of the train operating company social media team became real for everyone, and was celebrated.

What is perhaps lesser known is that Southern Railway were pioneers of exactly this sort of openness and transparency.

What is perhaps lesser known is that Southern Railway were pioneers of exactly this sort of openness and transparency.

The Southern Railway of the 1920s was embarking on a major upgrade to replace inefficient steam with electric trains. However the programme of works was causing a lot of disruption and there was no thought to communicate with passengers about what was going on and why. The newspapers had a field day.

John Elliot was a journalist first with the New York Times, and then with the London Evening Standard. There he learned the value of an organisation’s press office, first in the shape of American PR pioneer Ivy Lee at the New York Subway and second at London Transport, which didn’t suffer a bad press.

In 1925, Elliot was brought in by Southern Railway’s boss Herbert Walker, on the advice of London Transport’s chief Lord Ashfield. On being asked why he thought Southern was getting a bad press, Elliot remarked: “Well, I understand that you have no press office, so reporters can pick up any kind of story, and listen to all kinds of nonsense. You have got to reverse all this, and open up, and tell the world about your electrification.”

Elliot was hired, and became the first person in the UK to have “public relations” in their job title. More critically Elliot lay the foundations of a modern, professional PR programme.

He used a full range of media to get messages across, including press, posters, advertising and in-house magazines, all fully supported by open story-telling and frequent updates of progress. For the first time, this included actively hiring ex-journalists to quiz Southern critically from the passenger’s perspective and allow the railway to provide answers. This kind of openness continues on social media today. Insight into big engineering projects is also still fashionable – think of all the positive coverage that Crossrail gets.

Elliot also integrated the PR with marketing to boost ticket sales and put bums on seats of the trains to help repay for the electrification programme.

He developed a public affairs team to lobby government to help Southern compete with the emerging motor car. All through this he insisted on reporting directly to the general manager Herbert Walker, and so was a genuine part of the leadership team.

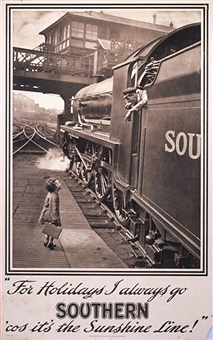

In addition to this openness and honesty, Elliot introduced the human touch. Water colour paintings of peaceful and serene views across Kent, Sussex and Hants were the equivalent to Eddie’s tweets for feel-good branding. Others appealed to the inherent romance of railways such as the one featuring a boy looking up at the driver with the caption “For Holidays I always go SOUTHERN ‘cos it’s the sunshine line!”

Elliot’s success led to him holding leadership roles in British Railways, London Transport and Thomas Cook, and he was made a knight.

The shrewdness of #AskEddie is a continuation of that openness, honesty and transparency in a human voice. The railways are part of our national conversation, and are both loved and loathed in the same breath, but this week, Southern rediscovered its PR mojo, bequeathed by the UK’s first ever public relations officer, and deployed by a PR master in the making.

Further reading

Sir John Elliot, On and off the rails, (1982) – autobiography

Shirley Harrison and Kevin Moloney, Comparing two public relations pioneers: American Ivy Lee and British John Elliot – from Public Relations Review 30 (2004) 205–215